Reclaiming & Centralizing Indigenous Knowledge in Schools with Linda Young

Today, we proudly introduce Dr. Linda Young (BA'94, BFA'98, MEd'20, PhD'2023), a dear friend and former doctoral student of Debbie's, who earned her doctorate in October 2023 using video conversations with thought leaders as an alternate form to a written dissertation. While Linda's unique and captivating doctoral dissertation expertly told her story, we felt compelled to dig deeper and uncover more about the person and the narratives beneath, and intertwined within, these conversations. "I don't know if Debbie has mentioned, I'm a bit of a storyteller," she warned us. Not only is that statement true, but it's the exact reason that we are enormously thankful for the opportunity to listen. We invite you to do the same as we share our conversation with Linda, an exploration of her video conversations: The Journey of a kêhtê-aya (elder): kiskisi sôhkisiwin, tâpôkêyimoh, sôhkitêhê, nâkatohkê: Memorize the Strength, Have Faith, Have a Strong Heart, Pay Attention.

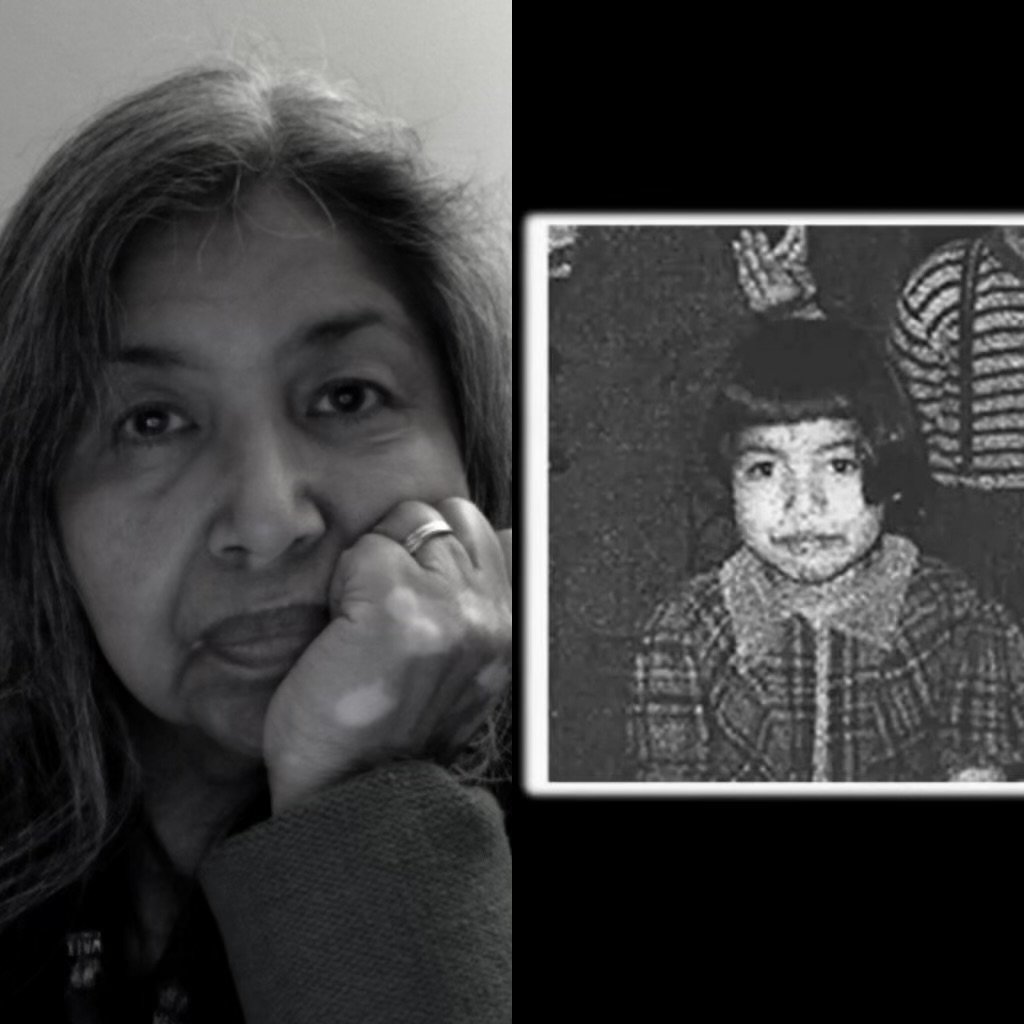

Who is Linda Young

Linda is a storyteller, but her identity encompasses much more than that single descriptor. Mary Ann Linda Young speaks Plains Cree 'Y' dialect and hails from Onion Lake Cree Nation. She is a residential school survivor, a Traditional Knowledge Keeper, kohkom, a friend, a student, an artist, a mother, and a grandmother. Much of Linda's life, identity, and dissertation are built upon a foundation of storytelling. "Where I'm from, what I've done, and who I'm connected to foregrounds everything that I do in my life," Linda explained. When asked about her professional background, she told us that she doesn't really understand the distinction because, for Linda, "personal and professional are the same thing." As you'll see in Linda's work and, in fact, in everything she does, it is all deeply personal.

Onion Lake Cree Nation lies just north of Lloydminster. "My reserve is right on the border of Saskatchewan and Alberta. If you were to drive up Main Street Lloydminster, you would end up in Onion Lake. That's where I'm from," Linda told us. "I left Onion Lake when I was 16. I'm a residential school survivor. I went to residential school for 10 years, from the time I was five until ten years later, and then I left after that and have not returned since except to visit." She informed us that her band is very large, with over 6,000 members including herself and her children. In the area, there were three ROMAN CATHOLIC residential schools. The first two were burned down, and the final one was there for quite a few years. "My grandparents, my mom, my aunties, my uncles, and I all went to that residential school. So, there are four generations. My grandfather, my mom, and I all had the same kindergarten teacher. This is key and all really connected to the work that I do and did in my dissertation. You can think about all of the families, the generations of families that have been impacted by residential schools. When you read about the stuff that's happening in residential schools, all those generations have been impacted."

Linda illustrated this further with what she refers to as her "intergenerational trauma tree." Looking to her mother's side of the family, this tree begins with her grandfather, the one who had the same kindergarten teacher in residential school as Linda and her mother. He had 18 children and two marriages. There were 85 kids from those 18 siblings, 406 grandchildren from those 18 siblings and 812 great-grandchildren. "And I'm only talking about three generations here," said Linda. "So, the total number of family members that were impacted by our residential school was over 1,300." Linda told us that this is just an example of the impact of intergenerational trauma that is connected to her as a survivor. "That's why residential schools play a very important part in any work that I do because it's part of my life, identity, and my experience as a student."

"I don't reject what I learned in residential school, but I reject what I was told."

She noted that "once you entered the doors of the residential school you became a ward of the government and your parents no longer had a say in what became of you. When I was in residential school, we were told every day that who we were and where we came from was not a good way. And so part of the reclamation process is recognizing that indeed our way of life and our way of doing things is good."

Many Forms of Education

In her late teens, Linda pursued education to upgrade her skills because she hadn’t gone to high school. She underwent an upgrading course at an institution in Regina and attended university there. "My first university experience was actually not as a student but as a person who tagged along with my ex-husband, who was doing his master's at the time. I was new to Regina and very young, so I would just go with him. It was my first exposure to university, and I loved the energy, the way people were talking. I didn't have a clue what they were saying, but I liked it." For Linda, that's when she was "bitten" by the academia bug. Though that certainly wasn't her first experience with education itself.

"It actually comes from my great grandfather who said to me (in Cree and loosely translated) that in order for me to have autonomy as an Indigenous person I would need an education."

She noted that her interest in being a student and learning has always been because of the generations that came before her.

Linda pursued an Interdisciplinary Studies master’s program while also committing to participate in Sundance for four years. Both roles were intense, she reflected, "but I have a tendency to do that. I do things both ways. It's really a balancing act between living as an Indigenous person, having an Indigenous worldview, but also living in a world that is not Indigenous, that is an English, Western worldview. It’s always a balancing act for me in everything that I do."

Linda holds a BFA in Fine Arts. "The exhibition for my BFA was actually in painting, and the only reason I did that was because I am not a very good painter and I needed to find a way to challenge myself. I ended up painting in sort of an abstract expressionist area because it worked for me. The artwork I do is always narrative-based." She told us that most of her exhibit was about the Treaties, the negotiations, the misunderstandings, and the mistranslations.

Visual storytelling was also a key part of her Master of Education project in Curriculum Studies - Telling and retelling my residential school survivor story: What was lost, what replaced it, what is needed to heal, reconcile, and reclaim Indigenous education for the benefit of students, families and communities.

"At residential school, every boarder had a job to do. The sister said to me that if I finished my work early, I could spend the rest of the afternoon looking at View-Master slides. There were a dozen boxed sets on the table – so many choices. I spent my winter in the sewing room sitting by the window with the View-Master in hand. The three-dimensional effect of looking through View-Master slides invited me into a world that I would otherwise not have known existed. Classroom learning in residential school was mostly angst-ridden, so I treasured my self-directed history and social studies lessons on Saturdays," Linda explained in her project’s abstract. Given its significance, she used the View-Master as the portal into her residential school story. Her project was captured in a long and short video.

"My hope is for people to use the videos for the purpose of educating themselves and others about the residential school experience. It's important for me to be able to share the story in a way that is effective but doesn't cause a lot of pain. That's my intent. I don't share the stories that are heartbreaking because I'm not there to help close whatever I open in terms of pain. In the video, I talk about the 10 steps and what they represent. Every residential school in Canada has steps leading up to the front door. Some have more or less than 10. Every step took me away from my land, my home, my family, my language, my culture, and my ceremony. Every step that I took towards those doors took my identity away."

Speaking about her body of work as a whole, Linda shared: "I am a residential school survivor, my family has been impacted by missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls and the 60s scoop. All of these things have impacted Indigenous people over generations, so there's a lot of stuff we can reclaim."

Linda refers to much of her work as "a reparative act. What I do is re-creation. For my BFA exhibition, I went into the past, I looked at history, and I created pieces to repair that time in history. The work I did in the dissertation piece, in the conversations, it all has to do with reclaiming language, culture, history, kinship, whatever it is that we lost–or was taken from us."

Linda’s Dissertation

"I started this journey with Debbie in 2017 because I heard her speak at a conference in 2016. It inspired me so much. For the first time, I actually heard somebody who was a non-Indigenous person talking about my experience in residential school, which was to be in an environment where there were rules that controlled who was allowed in and who (often a parent/caregiver) was kept out. I created art surrounding the gatekeeping and protectorate piece that Debbie talked about and I became very interested in talking to her further about it."

Years later, Debbie and Linda’s work in the parent engagement space has been transformational.

Linda's dissertation is based on four conversations. "My PhD research is based on my belief in healing, reconciling, and reclaiming Indigenous education to benefit students, families, and communities. There is a critical need to explore the role of Elders in schools. How are they used and positioned, by whom, and why?

How can the education system move away from inviting Elders to check box-type activities and progress to having Elders acknowledged as having integral and continuous roles in schools where their knowledge is central to shaping and informing the unfolding curriculum being lived out with children and families?" she explains in her dissertation’s abstract.

The project is comprised of 10 videos, four bookworks, a glossary of terms, and a gallery show. It was deeply important to Linda that her project was put forth in the form of a conversation rather than a defence as its purpose is not to fight back but rather to create a dialogue and a foundation for reclamation.

The four conversations within Linda's dissertation are:

Commodification, Urbanization, and Changing Role of Elders

Cultural Trauma

Artivism and Reparation

An Examination of Lived Reconciliation in Schools

“Debbie and I talked about the topic I wanted to look at originally. Because I was working as a Knowledge Keeper/Kohkom for the school division here in Saskatoon, I wanted to look at Elders’ roles in the schools and in the classroom. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal People talked about the importance of bringing elders back into the classroom because they are the original educators for children. So that was kind of my focus to begin with.”

Linda drew inspiration from the teachings of her mother, a central figure in her work. Guided by protocol, prayer songs, and the offering of tobacco, Linda's journey unfolded. Each day began with smudging and prayers, with tobacco leading her to engage thought leaders for conversations. This approach influenced her scholarly activities, decision-making, and interactions throughout her doctoral journey. Linda spent a year in the field as an Elder/kehtê-aya, documenting her experiences and research. Immersing herself in the role of an Elder/Knowledge Keeper, she committed to fulfilling protocol requests weekly.

To initiate discussions, Linda created bookworks, non-books that relied on viewer interaction to convey meaning. Each bookwork, taking six months to a year to complete, reflected extensive research and consultation with experts. Her video dissertation comprised ten videos, including introductions to her research journey, core conversations with thought leaders, and reflections. These videos, accompanied by transcripts featuring Cree language and translations, culminated in a gallery show at AKA Gallery, a community-based gallery in Saskatoon. This comprehensive approach, encompassing videos, transcripts, bookworks, and the gallery show, constituted Linda's doctoral dissertation. She supplemented her work with a glossary and bibliography for further exploration and understanding.

The Work of an Elder

In reflecting on her role as an Elder and the responsibilities it entails, Linda emphasizes the significance of recognition within her community. She shares, "No one can call themselves an elder. People recognize you as someone they can go to and offer protocol." Accepting tobacco symbolizes a commitment not only to a conversation but to a journey together, echoing her mother's teachings on commitment. Despite initial uncertainties, Linda embraced this responsibility, guided by her mother's wisdom and the desire to honor her teachings.

For Linda, the essence of being an Elder lies in following protocol and relying on prayer and guidance. She recounts, "I started with following protocol from day one." Each step, whether approaching someone for guidance or inviting participants to conversations, was preceded by prayers and offerings. This approach ensured alignment with her spiritual elders and provided clarity on the path forward.

Throughout her journey, Linda's reliance on protocol remained steadfast. She explains, "I wouldn't do anything without doing that. I wouldn't say things without doing that." This adherence to protocol not only guided her actions but also reaffirmed her faith in the process. By integrating these practices into her dissertation and daily interactions, Linda embodies the wisdom passed down to her and embraces the responsibilities of an Elder with reverence and humility.

What’s Next?

When asked, "What's next?", Linda responded, "I just keep going. The work is never complete, because the story goes on, right?"

Her goal with the work from her dissertation was to reach everyone. "As for me, I work for the community. I am here to be of service to the community.”

Looking ahead, Linda envisions a future deeply rooted in community service and knowledge sharing. She articulates, "If my granddaughters want to access my knowledge, they can come, and do that." Embracing her role as a grandmother to all, Linda welcomes individuals into her home, fostering connections and imparting wisdom. Her commitment to community service is unwavering, with a focus on leaving a legacy of knowledge and understanding.

Reflecting on her academic journey, Linda sees her dissertation and associated work as integral components of this legacy. She explains, "My reason for doing the Master’s and the PhD is to leave that knowledge in the archives." By ensuring her research is preserved and respected within academic institutions, Linda seeks to preserve Indigenous stories and experiences for future generations. This dedication extends beyond academia, as evidenced by her efforts to document her residential school story and share it internationally through installations.

For Linda, the various facets of her work intertwine seamlessly, forming a cohesive narrative of her life's mission. She emphasizes, "This work is not separated from me. It's all together." Whether through academic research, artistic expression, or community engagement, Linda's endeavours converge to create a lasting impact. As she looks to the future, Linda remains committed to weaving together her diverse experiences and contributions, ensuring they work together harmoniously to uplift and empower others.

The Power of Parent Engagement

Parent engagement in Indigenous education is paramount for the holistic development and success of Indigenous students. Linda emphasizes the importance of reclaiming power and knowledge within Indigenous communities. She underscores the intergenerational impact of historical trauma and the need to rebuild trust between parents, schools, and students.

Drawing from her personal experiences, Linda reflects on the challenges Indigenous parents face in trusting educational institutions. Despite her family's involvement in education, Linda attended parent-teacher meetings not out of curiosity about her children's curriculum but to ensure fair treatment and accountability from educators. This sentiment highlights a broader issue of systemic mistrust stemming from the legacy of residential schools.

For Linda, reclaiming Indigenous identity and knowledge is central to empowering Indigenous parents and students. She emphasizes the role of family in education, noting, "Family is the aunties and uncles, grandparents. And the parents who are educating are part of the educational process." This inclusive approach recognizes the importance of cultural transmission within familial networks.

Furthermore, Linda advocates for the incorporation of Indigenous knowledge and practices within educational frameworks. She stresses the need to centralize Indigenous perspectives, not merely as a token gesture in the library but as an integral part of curriculum design and pedagogy. By foregrounding Indigenous knowledge and language programs, schools can create environments that honour and validate Indigenous identities.

Linda's work aims to instill confidence and agency within Indigenous communities. Through her research and advocacy, she hopes to foster a renewed sense of trust and partnership between Indigenous families and educational institutions, empowering them to shape the educational experiences of future generations.

"My grandson comes over every day, and every day, he is learning Cree because I'm teaching him, so that's the way to do it is to reclaim it that way and practice it in the schools, from language programs through to land-based programs. And through foregrounding and centralizing indigenous knowledge in the school."